History of the Sedalia Museum

The following article was authored by Carole Williams and posted in the Sedalia View in 2016.

The early days of the Sedalia Museum start with the enthusiasm of one resident–and not even one of the many descendants of Colorado pioneers still living here. Its growth formed collaborations with other organizations, bringing Sedalia a wealth of activities and opportunities seldom found in a small unincorporated village.

Long-time Sedalia resident, Barbara Machann was concerned that her town’s history was vanishing. Barbara’s family, the Belfields, moved to Sedalia in 1950, buying Nel Anderson’s ranch just west of the present day elementary school. As office manager for the West Douglas County Fire Protection District (WDCFPD), Barbara met many of the town’s residents, including descendants of original homesteaders. She was a firefighter for the district from 1980 to 1989 and then became the dispatcher.

In 1982, to celebrate the town’s centennial, Barbara compiled a small booklet titled Sedalia 1882 – 1982. Known as The Blue Book, it contained photos of early homes and businesses, and information about early days of the village.

Barbara continued to collect historical information, which grew to fill an entire carton–but there was no real place to house the material. A few other local women, including her sister Pam Belfield, became interested in helping. But it wasn’t until February 7, 2000 when a group of history enthusiasts began meeting regularly at Fire Station #2. They set a goal “To Protect and Preserve the Local History of Our Area”. Oral histories and photos the group gathered and shared with the history and research department of the Douglas County Library. The group successfully applied for status as a 501(c)3 non-profit organization.

As with so many of Sedalia’s organizations, the history group overlapped with other groups. The Robbinses, Meyers, and Youngs were all active in the WDCFPD, setting the stage for a collaboration between the two groups. As an unincorporated area, Sedalia has no governing body, and no tax revenue for community projects. The only “governing” groups at that time were the school, the fire department, and the Sedalia Water District.

Just about the time the history group formed, the WDCFPD broke ground on a new, much larger building. The former firehouse, a brick building, constructed in 1933, became the office for the office manager (Barbara) and the fire chief. The fire department used about a third of the building, and Barbara talked the board into letting the museum share the space.

The museum had its first home. The museum named The Sedalia Historic Firehouse Museum in honor of the landmarked little firehouse.

Through donations, they furnished it with display cases and the few artifacts they had collected. Most of the displays relied on items loaned by museum members.

The collaborations with WDCFPD made the museum’s growth possible. The fire department charged no rent and paid all utilities–perfect for an organization with few members and no income!

Completion of the firehouse brought another important collaboration. The new station was surrounded by bare land. One of the board members, Kelli Fallbach, a new Master Gardener and a museum member, suggested approaching the Colorado State Extension Douglas County Master Gardener’s Program. The firehouse/museum gardens became one of the accepted Extension Office projects, which meant that Master Gardeners could work at the fire station for their required volunteer hours–an instant gardening staff! The fire department installed a lawn sprinkling system, and paid for the maintenance of the lawn areas, while local gardening enthusiasts and Master Gardeners established garden areas to make the fire station’s new building an attractive part of Sedalia and an educational tool to show local residents plants that flourish in the Sedalia intermountain area.

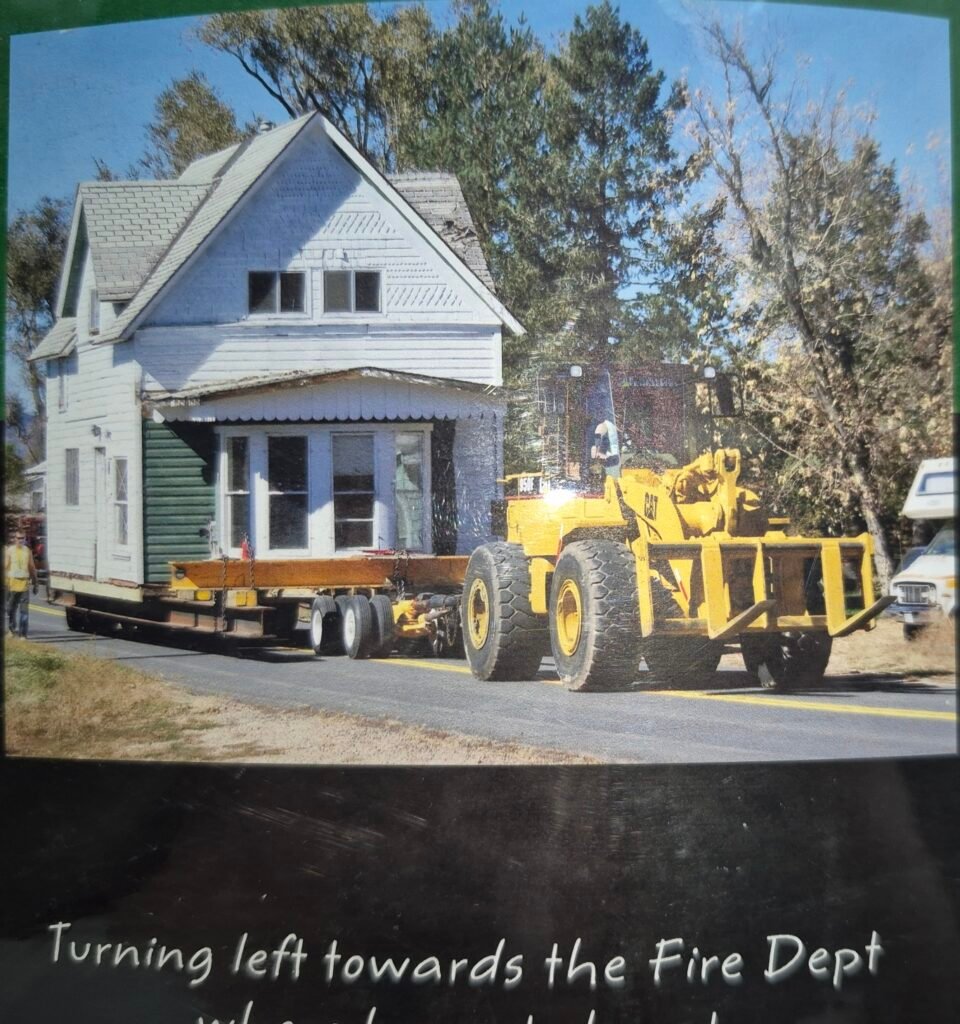

One day, Barbara was pulling weeds in her pasture and noticed the small, dilapidated cottage behind Gary Sutton’s home. An idea began to take root. She approached the Suttons who offered to sell the house to the museum for $1, with the provision that it be moved. The project was first broached in the September 2005 museum meeting. At that time, the organization had fewer than 20 members, with about half of them active. Most were at or near retirement age.

There’s a joke among Sedalia Museum’s earliest members: “If someone offers to sell you a house for a dollar, run!”

The proposal to acquire a house ushered in a time of conflict, learning, and creativity for the fledgling historical group. Not everyone wanted to tackle this little house. (The author of this article was one of those most strongly opposed.) After years of being a rental, the house sat many years sitting vacant, victim to the weather and to local wildlife. Rodents lived in the walls. Windows were of various sizes and materials. But it retained its Victorian fish-tail shingles, original to the house when it was built by ranchers Mary Ann and Willis Bryant. The building itself was 18 by 24 feet, with a 6 foot circular bumpout.

The fire department offered to put the building on its Sedalia property. At first the plan was to put the house to the west of the new fire station. Further investigation revealed many underground utilities, the hub of Sedalia’s communication system.

Fortunately, at that time, the state agreed that the fire department could fill in the deep and unsightly barrow pit (water run-off reservoir) to the east of the property, and museum members began to investigate that site. By this time, the museum had so many questions for the fire department that Fire Chief Terry Thompson began to refer to the museum members as “The War Department”.

All that remained was to get the correct documents from the county and raise the money, originally estimated at about $36,000. At that time, the museum treasury had just under $5,000.

The museum board was just about to get a lesson in local politics. Applications to the Douglas County Planning Department were prepared — and promptly rejected. Rules, they said, required two handicapped bathrooms, in an 18′ x 24′ building! Setback rules, zoning, materials — the things the museum couldn’t do were endless.

Undaunted, Project Manager Machann researched each “no” item, and came up with a rebuttal. The Organization of Front Range Museums, a coalition of small museums, helped out. They pointed out that the venerable Molly Brown house does not have public restrooms — they are housed in a separate building. The fire department agreed that the fire station bathrooms could serve the museum well. The list, with solutions, was returned to the Douglas County Planning Department.

Shortly, a second list arrived, along with a whole new set of reasons why moving the building would not work. That was the turning point for the museum board. They were so deeply offended by the obviously spurious regulations, that they became even more determined, giving rise to the often used expression “Don’t p— off the little old ladies of Sedalia.”

Kelli Fallbach, who was appointed to oversee the construction phase, took the fight directly to the county commissioners. Very shortly, the project was approved, and the Philip S Miller Foundation gave the museum a $10,000 grant, with an additional $5,000 matching grant. They were the first of two such grants from the Foundation. Surprisingly, within several months, the Douglas County Planning Department office was restructured, with several high-ranking officials dismissed. Now all that remained was to make decisions on the house restoration, and raise the money. So the board learned a new trade — fundraising.

Bake sales and garage sales just weren’t going to do it. It was clear the museum board needed to think in larger terms. The author of this article had a background in grant writing, so the group began to research possibilities. One stumbling block was that the museum had no financial track record. It had no stable income, no paid staff, and no regular expenses. Foundations tend to take a dim view of making grants to a group with no proof that it can handle money.

While the fund-raisers put their heads together to present a good case for their cause, the rest of the museum members were hard at work with the details. Bit by bit, money became available to dig the foundation, move the building, and begin restoration.

So many changes had been made to the house over the years that the museum group decided to restore it in the spirit of its 1890’s look. The fish scale siding on the gables, one of the few remaining original features, has been preserved. A new, larger porch accommodates a handicapped ramp, while an addition on the north side houses stairs to the basement.

The decorating committee, Barbara Robbins and Carole Williams, had a great time selecting colors for the Victorian cottage. Roofing chairman Deby Williams researched and selected shingles with an old-time look. Construction supervisor Kelli Fallbach acquired the services of contractor Jack Hallett, whose family moved to Douglas County from New England. His invaluable advice set the stage for everything from basic construction to authentic trim details.

Permission to use the fire department’s restrooms saved the group from having to install plumbing and pay water tap fees. Further economy became possible by the donation of electric baseboard heaters from Elver and Barbara Robbins, so no gas line or tap fee was needed.

Contractors entered into the spirit of the remodel, offering discounts and helpful tips. Elver Robbins stripped untold layers of paint from the original oak fireplace mantel, and museum members painted interior trim. Local residents were generous in their gifts, “purchasing” windows, porch posts, and doors.

Equally successful, the fund-raisers secured grants from major foundations, including El Pomar, Philip S. Miller Foundation, Gates Rubber Company’s Foundation, Historic Douglas County, and Kowalski Family Foundation. Because the house no longer sat on its original site, it did not qualify for historic restoration funds.

Moving into the little house brought regular expenses for the first time: electric bills and insurance. In 2015, the museum hired its first employee, Katy Oja, to enter all of its records and documents into the computer.

During the house restoration project, the museum wasn’t losing sight of its mission—historical information. Barbara Machann, Bev Larsen and Douggie Young gathered information for a series of books on Remarkable Ladies of Sedalia. Eventually, the series was extended to six volumes, then condensed into a hardback edition. Now biographies are being collected for a “Remarkable Men” book. Barbara also compiled a color photo book, Historic Barns of Douglas County, documenting a number of the old barns in the area. Revenue from the books continues to bring income to the museum.

Award-winning songwriter Junie Fisher researched her family’s history in Douglas County, and issued a CD, “Gone for Colorado,” featuring songs inspired by her findings. The museum hosted two fund-raising concerts featuring Fisher, and sells the CD in the museum.

Being one of the few official organizations in Sedalia gives the museum a unique position, offering the opportunity to help local residents in various ways. When the Old Town Sedalia Merchant’s Association disbanded in about 2005, the Museum took over the Sedalia Merchant’s Directory, a listing of local businesses—and coincidentally, another good fundraiser.

In 2011, museum members became frustrated by the lack of publicity from Denver and Castle Rock newspapers. Press releases were sent, but seldom published. The obvious solution? Start a newspaper. Many Sedalia are residents are elderly and don’t use computers, while the mountainous terrain makes internet reception difficult for others. At a time when many print newspapers were giving up the ghost, the Museum deci

At a time when many print newspapers were giving up the ghost, the Museum decided to launch a print publication, the Sedalia View. Through ad sales, today in 2016 the publication is self-supporting.

As the museum’s membership evolves, so do the projects it undertakes. For the past three years, a group of enthusiastic museum gardeners has raised heirloom tomatoes and sponsored a sale raising about $3,000 annually. Just for fun, there is a tomato tasting day in the late summer to evaluate the crop.

When the final tally for restoring the museum was in, it totaled nearly $150,000—and produced an entire cadre of Sedalia women who now believe that nothing is impossible.

Moving the cottage